Canne de combat is a French martial art that involves the use of a cane or stick as a weapon. Originating in the early 19th century, it evolved from techniques used for self-defense into a codified sport. The practice includes swift strikes, feints, and agile footwork, making it a dynamic and strategic form of combat. It is recognized for its particular emphasis on speed, precision, and fluidity of movement, often resembling a choreographed dance more than a brutal confrontation.

As a sport, canne de combat is governed by rules that prioritize safety and sportsmanship. Participants wear protective gear and the canes used are lightweight, designed to ensure that the strikes are non-lethal. The objective in competition is to touch the opponent with the cane while avoiding being touched oneself. Points are scored based on the target area, with different parts of the body being worth varying points. The sport is practiced both recreationally and competitively in France and has a growing community of enthusiasts worldwide.

Canne de combat training not only hones an individual's fighting skills but also enhances coordination, agility, and overall physical fitness. It demands a high level of discipline and precision, encouraging practitioners to master control over their body and the cane. Through regular practice, canne de combat offers a unique blend of physical exercise, artistic expression, and tactical challenge. It is an embodiment of tradition and modern sport, providing a glimpse into the rich history of French martial arts.

History

Canne de combat, a traditional French martial art, has a rich history tied to both self-defense and sport. Its origins date back centuries, with a significant evolution leading to modern practices observed today.

Origins

The origins of Canne de combat can be traced to 18th-century France, where it started as a form of self-defense. The canne (cane) was a common accessory at the time and thus became a practical defense tool for the upper class.

Evolution and Development

In the 19th century, the martial art evolved with the influence of Master-at-arms who refined the techniques. It has been practiced as a sport discipline since the 1960s and is part of the French Boxing Savate Federation. The sport aspect gained prominence with the influence of individuals like Louis Merignac, who introduced structured rules and organized competitions.

Key individuals:

- Joseph Charlemont: Contributed to the codification of the discipline in the late 19th century.

- Maurice Sarry: Revitalized the sport in the 1970s with new techniques.

Milestones:

- Early 20th century: Inclusion in physical education within the French military.

- 1978: Establishment of the French Federation of Canne de Combat and Associated Disciplines.

Equipment

In Canne de combat, specific equipment is essential for both offense and defense. The right gear ensures safety and adherence to competition rules.

Canes

Canes used in Canne de combat are typically made from lightweight, flexible materials such as rattan or chestnut wood. They measure about 95 centimeters in length and have a rubber tip for safety. The cane's specifications are:

- Length: 95 cm

- Weight: Around 90 to 130 grams

- Material: Chestnut wood

- Tip: Fitted with a rubber end

Protective Gear

Combatants wear protective gear to prevent injury during matches. The essential items include:

- Gloves: Padded gloves to protect hands, often with reinforced knuckles.

- Helmet: A fencing mask or a helmet with a visor to safeguard the face and head.

- Chest Protector: To shield the torso from strikes.

- Shin Guards: For leg protection against missed cane swings.

Participants may also wear arm guards and a genital cup for additional safety. This gear is mandatory in official competitions to maintain a high standard of participant protection.

Techniques

In Canne de combat, practitioners utilize a range of techniques for offense and defense. Mastery of these techniques requires precision, agility, and strategic thinking.

Six fundamental strikes

Canne de combat features several basic strokes aimed at specific target zones.

- Latéral extérieur (high/median/low): armé behind the head on the armed‑hand side; the cane performs a horizontal moulinet from left to right; the pelvis pivots and development is staged wrist → elbow → shoulder so the arm is extended at touch.

- Latéral croisé (high/median/low): armé behind the head on the non‑armed side; the moulinet runs right to left; pedagogy mirrors the exterior lateral with pelvic pivot and staged development.

- Brisé: armé at trunk level; vertical moulinet clockwise; the hand opens slightly to let the cane turn; extension is piston‑like and must reach full extension at touch.

- Croisé tête (croisé haut): armé at hip level on the non‑armed side with the tip down; vertical rotation from bottom to top; a slight elbow flexion is permitted during the hand’s passage to protect joints; the arm must be extended at touch.

- Enlevé: armé at trunk level; vertical moulinet counter‑clockwise; extension begins after the hip plane and reaches full extension at touch; used for low‑line attacks when the tip passes beyond the foot.

- Croisé bas: armé above and behind the head with the tip up; vertical rotation from top to bottom; development is performed with the arm extended at touch and pelvic pivot to avoid spinal torsion.

Trajectories must remain consistent: abrupt changes beyond the last quarter of rotation are not permitted. The direction of the moulinet distinguishes some techniques (for example, brisé versus enlevé).

Execution of each stroke requires the canneur to maintain proper form, with a fluid motion originating from the shoulder and extending through the arm, wrist, and cane.

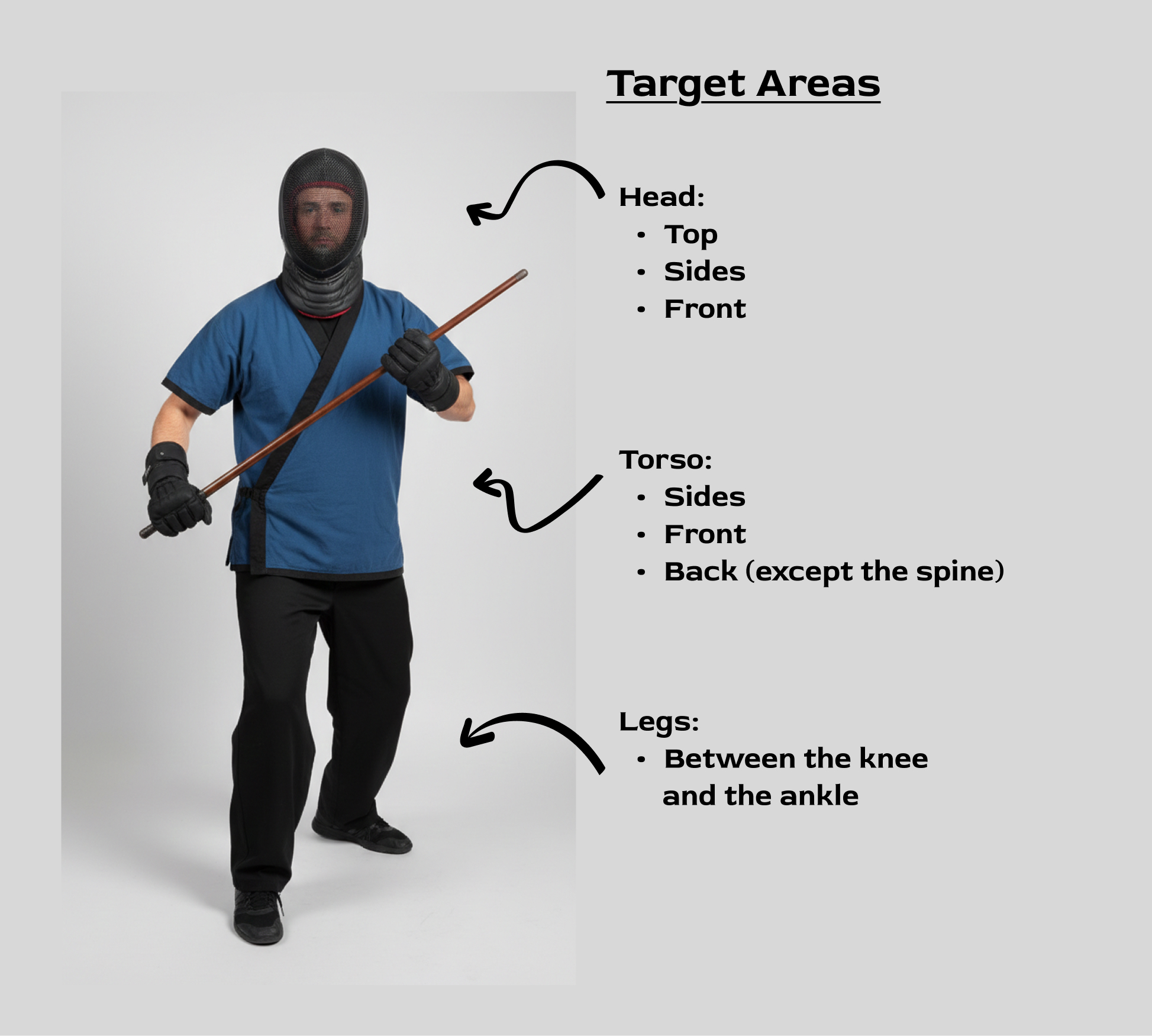

Target zones

Target zones are precisely delimited into three lines. The high line covers the head and face but explicitly excludes the neck, nape and back of the skull. The median line includes the frontal abdominal belt and the lateral torso between the iliac crest and the xiphoid line, with the dorsal area allowed in extension of the frontal zone. The low line covers the leg area between the knee and the malleolus; within that low zone there are no forbidden sub‑surfaces. A valid touch must meet observable technical criteria: it must land with the striking end (the upper quarter) of the cane, occur inside an authorized zone, be clean and controlled, and take place with the cane aligned with an extended arm. Trajectories must lie in a plane tending toward horizontal or vertical depending on the technique, and excessive closure of the arm‑to‑torso angle is discouraged for safety.

Defensive Moves

Defensive techniques in Canne de combat are just as vital as offensive ones. A canneur must anticipate and parry incoming attacks using a series of maneuvers. They also need to be agile, moving in and out of range effectively.

Parries are executed on the opponent’s weapon and are designed to protect up to two authorized surfaces. Lateral parries and crossed lateral parries defend against horizontal attacks by placing the cane vertically in front of the protected surface; they can be oriented for high or low lines (tip up or tip down). Vertical parries place the cane horizontally above the head to defend vertical attacks; exterior or interior variants depend on hand placement. Inverted lateral parries, total parries and other variants are also used, but the constant rule is that parries act on the opponent’s weapon and must preserve visibility of valid target zones. Practical recommendations for parries include keeping the armed hand close to the body to shorten the recovery path for an immediate riposte, avoiding masking valid targets with the parry, and pivoting to accompany the parry and anticipate the riposte armé.

Each defensive move must be executed with precise timing to successfully deflect the attack and create an opportunity for a counter-strike. Having a robust defense not only protects the canneur but also sets the stage for effective retaliation.

Core technical philosophy

Two simple but fundamental principles govern the practice. First, the sequence parry or evade, then riposte is mandatory: a practitioner must defend by parrying or evading before attempting to score. Second, the notion of priority is central: the competitor who reaches the preparation position (the armé) first gains priority; a defender who re‑arms immediately after a defensive action can recover priority if the opponent has not re‑armed more quickly. Conventions assume a right‑handed practitioner: the armed hand is the “main armée,” the armed side is the “côté extérieur,” and the opposite side is the “côté croisé

Preparation and mechanics of attack

Every attack begins with an armé, a dynamic preparation that is part of the technique rather than a static pose. The armé both readies the weapon and establishes priority. Horizontal attacks (the lateral family) typically place the hand behind the head with the cane tip forward and follow a wide, mostly horizontal circular path; vertical attacks use hip‑level or overhead preparations and follow vertical circular paths. For the brisé and the enlevé the armé is at trunk level and the cane rotates in a vertical moulinet; thrusts are explicitly forbidden.

A consistent body mechanic is the pelvic pivot: shoulders and pelvis should move together during armés and developments to avoid torsion of the spine. Slight heel lift is recommended to reduce knee torsion. The cane is held relatively tight in the hand while the wrist rotates to generate the moulinet; development of the strike is often initiated with the wrist, then the elbow, then the shoulder, so that the cane is in line with the extended arm at impact.

Footwork and displacement

Footwork is integral and strictly regulated. Only the feet may be used as supports. Fente avant (forward lunge) is the preferred method for low‑line attacks: the front leg is bent (the knee must not touch the ground), the front thigh may be raised up to 45° above horizontal, and the rear knee remains slightly flexed; weight is shared between both feet and the feet are not placed on a single line to preserve stability. Fente latérale and fente arrière are permitted under the same stability rules, with lateral lunges preferred over rear lunges. Flexion involves bending both legs without changing support and lowering the pelvis at least to knee height; grand écart is the full split position.

Elementary displacements include esquives (dodges), décalages (shifts) and traversées (passing around the opponent). Voltes are turning maneuvers that change side and create offensive opportunities; they may be combined with hand changes and must finish in guard at distance of touch. The manual repeatedly stresses coordination between displacement and attack: attacks should be timed with movement, voltes should be used to create openings, and balance must be maintained to enable immediate riposte after a parry.

Safety, pedagogy and judging implications

Safety is embedded in every technical prescription. The pelvic pivot and slight heel lift protect the spine and knees; small elbow flexions are allowed to protect joints during hand transitions; dangerous techniques such as thrusts are forbidden; and trajectories and contact points are defined to ensure touches are controlled and observable. Because touches must be clean, controlled and made with the striking end of the cane while the arm is extended, the technical rules also serve as the basis for judging: they provide objective criteria that judges can apply to validate or invalidate touches and to adjudicate priority.

This approach to canne de combat frames the art as a system where weapon mechanics, body alignment and footwork are inseparable. The sequence of armé → development → touch → recovery is the structural backbone of every action. Pelvic pivoting, controlled moulinets, precise lunges and disciplined parries create a practice that is at once safe, technical and competitive. For practitioners and coaches the emphasis is clear: train integrated movements, respect the target zones and validity criteria, coordinate feet and cane, and always prioritize safety while developing speed and precision.

Progression and grading in Canne de Combat

Canne de combat training follows a clear, safety‑first progression: students move from cooperative drills to applied techniques and finally to controlled opposition. The French system uses coloured pommeaux (blue, green, red, white, yellow) to mark technical progression. Each pommeau is assessed across three modules—typically a mix of movement, technique/tactics, and theory—and candidates must reach the required average in each module to pass.

At the blue level students master guard, basic footwork and the six fundamental attacks and parries. Green adds distance control, voltes and hand changes. Red focuses on tactical actions such as traversées, immediate ripostes and feints. White emphasizes counter‑attacks, non‑dominant‑hand assauts, arena management and basic refereeing. The yellow grade is a regional/league‑level award requiring demonstration of mastery, coaching ability and an additional staff or double‑cane demonstration; specialty grades (defense, chausson, Joinville bâton) can provide bonus points.

Assessment prioritizes ability to apply techniques in context rather than rote repetition: examiners score specific, observable criteria (movement quality, correct target, continuity of sequences, parries, tactical choices). This approach aims to produce fighters who are technically sound, tactically aware and safe in opposition.

Canne de Combat and bâton arbitration and competition rules

The following information is a summary of the official arbitration and competition rulebook for canne de combat and bâton, now overseen by the Fédération Française de Savate’s Commission Canne & Bâton (formerly under the CNCCB). It reads as a practical manual for everyone involved in an event — officials, organizers, fighters and seconds — and its tone is prescriptive: safety, fairness and the preservation of the sport’s image and ethics are the constant priorities. From the preamble onward the text makes clear that anyone participating in a federation‑sanctioned competition accepts the technical, medical and arbitration rules and the ethical code that accompanies them. The rulebook lays out who does what, how matches are organized and timed, how the arena and equipment must be prepared, what protections are mandatory, and how judging, sanctions and appeals are handled.

Officials, their responsibilities and the organizer’s role

At the heart of the system is a formal delegation of officials. The Delegation Official (D.O.) is the federation representative for the event and carries broad authority: verifying fighters’ equipment and the exact marking of the competition area, assigning judges and referees, evacuating hazards near the arenas, keeping administrative records (results, incident reports, judge bulletins), organizing the order of bouts, calling and presenting fighters, checking and counting score sheets, announcing results and additional reprises, receiving and processing written complaints, and, when necessary, stopping or suspending an assaut. The D.O. may be assisted by a responsible member of the refereeing body or by area managers and may delegate some tasks to a “délégué aux tireurs.” The D.O. also has the power to issue yellow or red cards to fighters or seconds for the reasons defined in the arbitration rules.

The referee is the in‑bout authority. He or she must be at least of the level required by the competition and is responsible for enforcing technical, sporting and arbitration rules during the assaut, for ensuring the safety and correct conduct of the fighters and their seconds, for checking equipment and the presence of seconds before the bout, for ensuring judges and timekeepers are ready, and for applying the timing protocols. The referee interrupts or stops confrontations when rules are breached or when safety is at risk, proposes warnings (which judges validate), and transmits the completed judge bulletins to the D.O. at the end of the last reprise.

Judging is carried out by three judges, chosen at a level at least equal to the competition. Judges must remain isolated at their posts and may only communicate with the referee under limited circumstances. They are responsible for counting touches that meet the validity criteria, validating or invalidating proposed warnings, participating in decisions about disqualification and resolving ties. Judge 1 also acts as the marker and may be assigned timekeeping duties if necessary.

Supporting roles include the timekeeper, who manages reprise durations, stoppages and rest minutes; the delegate to fighters, who assists the D.O. with administrative tasks such as equipment checks, bulletin distribution and result recording; and an official presenter who handles announcements and calls. The organizer is defined as the legal or physical entity authorized to stage the event and is responsible for all material organization: opening the venue on time, providing warm‑up space, ensuring public order, and complying with any convention signed with the federation. The organizer may recruit helpers for logistics and security, but the D.O. retains authority to limit their intervention. Failure to meet organizational obligations exposes the organizer to federation sanctions.

Competitors, seconds and administrative prerequisites

Competitors in canne de combat are referred to as “tireurs.” To compete they must hold a valid FFSBF&DA licence for the current season and present a medical certificate attesting absence of contraindication (CACI). The medical certificate is valid for three years provided annual QS‑SPORT attestations are attached and the athlete’s practice has been continuous. Entries must be made on official engagement forms by an authorized club representative and received before the closing date; late or informal registrations are not accepted. Organizers set registration fees and may require deposit cheques as guarantees; these cheques are destroyed after the competition unless the competitor fails to appear, forfeits without justification, or incurs fines or damages.

Seconds are mandatory for every assaut and must be adults licensed to the federation or an affiliated grouping. Their duties are practical and administrative: representing the fighter to officials, accompanying the fighter to checks, handling material problems during the assaut only at the referee’s request, advising the fighter during the minute of rest, and filing written complaints to the D.O. within the prescribed time (no later than 15 minutes after the decision). Seconds must remain seated in their assigned chair during reprises, remain silent and refrain from giving advice during active reprises; they may only leave their seat at the referee’s request or to fetch canes if necessary. Misconduct by a second is treated seriously: a second can receive yellow or red cards, be sanctioned for lateness, or be excluded if unlicensed.

The rulebook also addresses the participation of foreign competitors and those from federations affiliated to the FISav: they must present appropriate licences or federation authorizations, and for national competitions they follow the same engagement and fee rules as French competitors, with some procedural accommodations for documentation.

Match structure, timing and interruptions

Matches are organized into reprises (rounds) separated by one‑minute rest periods. The document provides category‑specific guidance for reprise durations and the number of reprises: younger categories and veterans have shorter reprises, seniors have longer ones, and the tables in the text indicate base durations, number of reprises and allowed supplements. These figures are presented as maximums and may be adapted by the competition’s specific regulations. In case of equality at the end of the scheduled reprises, additional reprises of the same duration may be organized after a one‑minute rest.

Interruptions are explicitly regulated. If an arrêt (stop) exceeds 30 seconds — for example because of medical intervention — the reprise is extended by 30 seconds; only one such extension is permitted per reprise. When multiple areas are managed by a central clock, an arrêt affecting one area may require synchronization adjustments so that all assauts resume simultaneously; if the stoppage does not concern the last reprise, the rest durations for unaffected assauts are increased so that all assauts restart together.

Team relay competitions follow a different model: they are typically conducted as a single reprise without prolongation, with total duration calculated from the base duration multiplied by the number of team members and by two; a single extra reprise is allowed in finals or semi‑finals after a one‑minute rest. The rulebook emphasizes that these durations are maxima and that organizers may set different limits within the competition’s regulations.

Arena, cane specifications and attire

The competition area must be a firm indoor sports surface and the combat surface is a continuous circle nine metres in diameter. If a band marks the limit, its outer edge must be placed at nine metres so the band is fully inside the combat surface; a preferred band width is five centimetres and a white colour. Within the circle the centre, the salute zones (30 centimetres long, located 1.5 metres from the centre) and the warning zones (40 centimetres long, placed midway between the two circles) must be marked. Judges and seconds are positioned at regulated distances and angles around the circle: judges two and three are placed 60 degrees to either side of judge one, seconds are placed at 45 degrees relative to the D.O.’s table, and the chronométreur sits at an independent table. The document notes that the presentation, start and end of assauts and the announcement of results are tied to these floor markings and that a plan is provided in the annex.

The cane itself is precisely specified. It must be a straight branch of dry chestnut wood, debarked and lightly polished, free of defects. The standard length is 95 centimetres and the weight range is 90 to 130 grams. A grip is permitted on the last 20 centimetres from the talon provided it does not add weight. Canes may be inspected and weighed before competition; any modification to a cane after it has been weighed is forbidden. Use of non‑conforming weapons exposes the competitor to sanctions under the arbitration rules.

Uniform requirements are detailed and strict. The jacket should have short sleeves covering between one‑third and two‑thirds of the arm, ideally reversible with each face bearing an official federation colour, and should extend to the hips. Trousers must reach the malleoli and a close‑fitting undergarment should be worn beneath them. Shoes must be appropriate for indoor sports. Both jacket and trousers are made of fully padded fabric to protect flanks, back and the full circumference of the leg; the pattern is to follow a federation‑approved patron. The full uniform is mandatory for all competition categories from under‑15s to veterans; younger categories may use a simplified kit (mask, gloves, shin guards and groin/chest protection). The pants must not reveal skin and visible adhesive tape is forbidden except by D.O. dispensation. Markings are allowed: the competitor’s name and club or regional insignia may appear without size limit, while sponsor logos are limited to two 10×10 cm squares on sleeves.

Mandatory protections, permitted extras and medical checks

Safety equipment is non‑negotiable. The mandatory protections include a fencing‑style mask with neutral grey or black mesh and a throat bib, a padded coiffe that covers the top, sides and rear of the head, gloves that cover the back of the hand, at least the first two phalanges of the fingers and the wrist (with fingers joined), shin guards, a male groin cup and a female chest protector with fully enclosed shells between fabric and lining. The groin and chest protections and shin guards must be worn under the uniform and must not be visible. Coiffe and gloves are to be made according to federation‑approved patterns. Competitors who present themselves without mandatory protections are not permitted to take part in the assaut.

The rulebook also allows certain additional protections: elbow and knee pads (worn under the uniform), ankle protectors, extra neck protection in addition to the helmet covering, and pelvic protection for women. The colours of helmet covers are regulated and must be two clearly distinct colours as defined by the federatioin, the D.O. and, if necessary, the organizer.

Medical prerequisites are explicit: the medical certificate confirming absence of contraindication (CACI) is valid for three years from date to date, provided annual QS‑SPORT negative attestations are attached for the intervening years and the competitor has practiced continuously. Organizers must ensure the availability of a room or space for first aid and the D.O. must ensure that a usable first‑aid room is assigned.

Judging, fouls, sanctions and dispute resolution

Judging is based on codified validity criteria for touches; three judges are responsible for counting valid touches and for validating or invalidating referee proposals for warnings. The rulebook defines a graduated system of sanctions: observation, penalty, warning, disqualification, and the use of yellow and red cards. Protocols for issuing cards, the motives that justify them, and their consequences are specified in the arbitration rules. Judges may be called upon to validate warnings and disqualifications and to advise the referee in cases of doubt; the D.O. records and processes complaints and may stop or definitively end an assaut if an external event or a serious incident occurs.

The document explains how winners are designated in normal and exceptional circumstances: by scoring according to the judges’ tallies, by additional reprises in case of equality, or by administrative decisions in cases of abandonment, forfeit, disqualification or exclusion. It also covers the tactical rules that affect scoring and priority: for example, the notion that the first competitor who “arms” takes priority and that priority can be recovered by an immediate riposte after a parade. These tactical principles are part of the theoretical knowledge expected at higher grades and are applied in adjudication.

Disputes are handled through formal complaint procedures. Seconds may file written complaints to the D.O. within the time limits set by the rules; a committee of appeal is designated to hear and decide on such claims. The D.O. keeps administrative records — meeting sheets, incident and accident reports, judge bulletins and the chronological display of the event’s progress — and these records support any subsequent appeals or disciplinary actions.

Practical implications

Taken together, the rulebook presents a tightly controlled framework designed to make canne de combat competitions safe, consistent and transparent. Every role is defined so that responsibilities do not overlap, equipment and arena specifications are precise so that contests are fair and comparable from one venue to another, and the sanction and appeals processes are formalized so that disputes can be resolved according to written procedures. For competitors and coaches the practical takeaways are clear: arrive with the correct licence and medical paperwork, bring a regulation cane and spare if possible, wear the full padded uniform and mandatory protections, and ensure the second understands the strict conduct rules and complaint deadlines. For organizers and officials the manual is a checklist of obligations: mark the nine‑metre circle and zones correctly, provide a warm‑up area and first‑aid facilities, assign qualified referees and judges, and keep meticulous administrative records. The document’s consistent emphasis on safety, fair play and the sport’s image underlines the federation's intent to preserve canne de combat as a regulated, ethical and technically rigorous discipline.

Other Martial Arts and Fighting Systems Incorporating the Cane

Bartitsu, established in England in the late 19th century, is a composite martial art known for integrating cane fighting techniques. Its founder, Edward William Barton-Wright, merged aspects of Jujutsu, Savate, Boxing, and cane fighting, resulting in a unique self-defense system that emphasizes adaptability and resourcefulness. Bartitsu utilizes the cane not just as a support tool, but as a weapon for strikes, locks, and throws.

In Filipino Martial Arts (FMA), specifically in Arnis, the cane doubles as an effective training tool and conventional weapon. While Arnis traditionally employs rattan sticks, practitioners apply similar maneuvers with canes, adapting stick techniques for self-defense scenarios. They use the cane for patterns of strikes, blocks, and counters, which are often reflective of the fluid motion common to FMA.

Japanese Kendo, known for its use of bamboo swords, or shinai, also sees an occasional adoption of cane techniques in practicing controlled movements and strikes. Although Kendo is predominantly sword-based, practitioners might use cane-like implements to refine their precision and technique outside of regular training with traditional Kendo equipment.

Bartitsu: Integrates cane techniques in a hybrid system that combines jujutsu, boxing, and savate.

Arnis: Utilizes the cane for strikes and defense, reflecting the fluid motion of FMA.

Challenges and Considerations

Canne de combat is a French martial art that involves two opponents using canes in a display of agility and technique. One must consider both ethical and legal implications when practicing or employing Canne de combat techniques outside of a sporting context.

Legal Considerations: The use of a cane as a weapon is subject to legal scrutiny.

- In many jurisdictions, there are clear definitions of what constitutes a weapon.

- Carrying a cane with the intent to use it for self-defense can be legally contentious if not conducted within the bounds of the law.

Ethical Considerations: The ethics of using a cane as a weapon stems from the intention behind its use.

- Self-defense: Using a cane to protect oneself may be considered ethically justifiable in cases of unprovoked attack.

- Assault: Employing a cane as a weapon in an assault is ethically and legally indefensible.

It is important for practitioners to maintain awareness of the ramifications of using their skills outside of a controlled environment. They should adhere to legal standards and ethical considerations, ensuring that their actions align with societal norms and personal integrity.

Combatpit.com extends its sincere gratitude to Adrien Le Mao, president of Kemper Canne de Combat Bâton et Savate (KCCBS) in Quimper, France for generously contributing valuable information that helped strengthen and improve this article.